Exploring Vision: The Mind's Role in How We Perceive the World

Written on

Chapter 1: The Mind's Eye

One of the most surprising insights in optometry is that our ability to see isn't solely dependent on our eyes. Jacob Liberman, in his 1995 book Take Your Glasses Off and See, highlights this unconventional idea. Liberman, who originally had 20/200 vision, challenged traditional beliefs by teaching himself to perceive with 20/20 vision, defying the norms of his profession. His central thesis is that ‘we do not see with our eyes!’

The essence of natural vision enhancement appears to reside in the mind rather than the eyes. Our thought patterns significantly influence our visual experience; even a simple shift in perspective can drastically alter what we perceive. As Goethe famously remarked on his deathbed, “Open the second shutter, so that more light can come in.”

Recent advancements in perception science echo Liberman’s claims. Andy Clark, in his book The Experience Machine, posits that human experience emerges from the intersection of informed predictions and sensory feedback. Essentially, what we perceive is largely constructed by our minds and is only adjusted by sensory data when discrepancies arise:

Human brains are inherently predictive. They evolve to recreate experiences based on a blend of expectations and real sensory information. For instance, upon waking, my subconscious predictions about sounds momentarily shaped my perception, leading to a fleeting hallucination that quickly corrected itself as more sensory data flowed in. This new information generated “prediction error signals” that aligned my experience with reality.

The conventional belief that information travels exclusively from the eyes to the brain is overly simplistic. In fact, there exists a significant reverse flow from the brain to the eyes and other sensory organs: ‘The quantity of neuronal connections transmitting signals backwards is believed to surpass the forward-moving connections by a considerable margin, sometimes by as much as four to one.’

Decades earlier, Liberman articulated a similar view, describing vision as ‘more of a projective process than a receptive one’:

What we perceive is heavily influenced—perhaps even dictated—by our beliefs. This perspective is not only valid but may be more fundamental. The saying “Seeing is believing” might be more accurately reversed to “Believing is seeing.”

What implications does this have for individuals with vision impairments? It suggests that removing glasses—what Liberman refers to as a crutch—could aid in learning to see without straining the eyes. However, this initial step can be challenging, as the brain’s preconceived notions (as Clark describes) often hinder progress: ‘If you perceive clear sight as a purely physical function of eye shape, that belief becomes a primary barrier to improving vision’ (Liberman).

Liberman contends that glasses artificially adjust vision, leading to long-term deterioration of the eyes. They not only narrow our visual field but also limit our perspective:

In ancient philosophies, “vision” transcended mere eyesight; it was equated with wisdom. Genuine wisdom, or what we often label as genius, arises from clear perception. The misconception that sight is confined to the eyes restricts not just our visual capabilities but also our entire worldview. The more we depend on glasses, the more we condition ourselves to judge our environment rather than truly experience it, thereby diminishing our innate ability to perceive its entirety.

Among Liberman's suggestions are various eye exercises (which are certainly worth investigating), particularly a technique he refers to as ‘Open Focus’:

Open Focus involves looking at nothing while observing everything. It embodies the effortless manner in which our eyes were designed to see. As you engage in Open Focus, you'll notice your eyes are in constant motion, never static. These movements represent the instinctive rhythm of vision, seeking out elements that demand your attention amidst the dynamic flow of life.

Artists have long understood the principle of Open Focus. Observing an artist stepping back to view her work, one might wonder what she is observing. In truth, she’s not focusing on anything specific; instead, she is softening her awareness, allowing her vision to encompass the work as a whole. She intuitively recognizes that an open gaze will guide her eyes to areas that require additional focus. When she steps back and her gaze flows freely, her work is complete. Open Focus can also be termed “nonjudgmental seeing,” as it grants equal significance to everything within our perception.

This artistic example is particularly relevant when we consider someone like Leonardo da Vinci, renowned not only for his exceptional visual acuity but also for his fascination with the concept of vision. His biographer, Walter Isaacson, notes:

His keen curiosity was complemented by his sharp eye, which focused on details that many overlook. One night, he observed lightning illuminating buildings, making them appear smaller momentarily, prompting him to conduct a series of experiments to verify that objects appear smaller when surrounded by brightness and larger in mist or darkness. He also noted differences in perception when viewing objects with one eye closed, leading to explorations of the reasons behind these observations.

Da Vinci was not only a painter but also an anatomist and a thinker, filling his notebooks with inquiries and illustrations about vision. For instance, he pondered: ‘Which nerve causes the eye to move such that the motion of one eye corresponds with the other?’

His deep interest in sight likely enhanced his observational skills—an important point Isaacson emphasizes when discussing perceptions of his talent:

Kenneth Clark described Leonardo’s “inhumanly sharp eye.” While a flattering expression, it’s somewhat misleading. Leonardo was human; the clarity of his observational skills wasn’t a supernatural gift but a result of his diligent effort. This insight is crucial as it suggests that we, too, can cultivate our observational skills through curiosity and intensity.

Isaacson mentions eye exercises akin to those Liberman suggests. For instance, one playful challenge involves having a friend draw a line on a wall while others, standing at a distance, attempt to cut a piece of straw to match the line's length. The closest measurement wins.

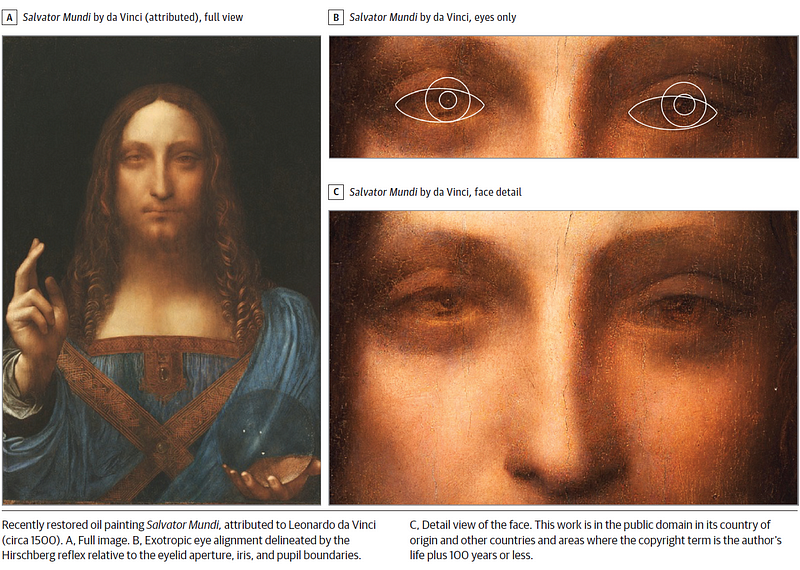

Interestingly, a recent study by optometrist Christopher W. Tyler proposes that da Vinci may have experienced a condition known as strabismus, which involves difficulty maintaining eye alignment on a focal point. Tyler suggests this could explain da Vinci's remarkable ability to depict three-dimensional solidity in faces and objects, as well as the distant depth of landscapes:

Intermittent exotropia typically allows for good stereoscopic vision when both eyes are aligned, but this condition permits its elimination when one eye deviates, leading to a suppression of awareness of the misaligned eye (thus avoiding double vision). This condition can be beneficial for an artist, as viewing the world with one eye facilitates direct comparison with the flat image being rendered. In contrast, stereoscopic vision provides the artist with a full understanding of three-dimensional space.

If Tyler's findings hold true and da Vinci indeed had a squint, this supports Liberman’s claim that visual impairments do not necessarily inhibit clear sight. As Liberman consistently notes throughout his work, despite now having clear vision, an objective assessment of his eyes would still categorize him as ‘moderately nearsighted and significantly astigmatic.’ Many eye care professionals would likely advise that he still requires glasses, despite his ability to see clearly.