# Einstein's Intriguing Relationship with Quantum Mechanics

Written on

Chapter 1: The Birth of Quantum Mechanics

Throughout my exploration of the evolution of quantum mechanics, from Max Planck's groundbreaking blackbody radiation law to the advancements in Quantum Electrodynamics by physicists like Dirac, Feynman, and Schwinger, I frequently encounter a common misconception. Many, particularly those outside the scientific community, assume that Einstein was fundamentally opposed to quantum physics. However, this perspective oversimplifies his stance. While it would be inaccurate to claim that he outright rejected quantum mechanics, it is fair to describe his relationship with the field as complex—characterized by both admiration and skepticism, particularly regarding its interpretations.

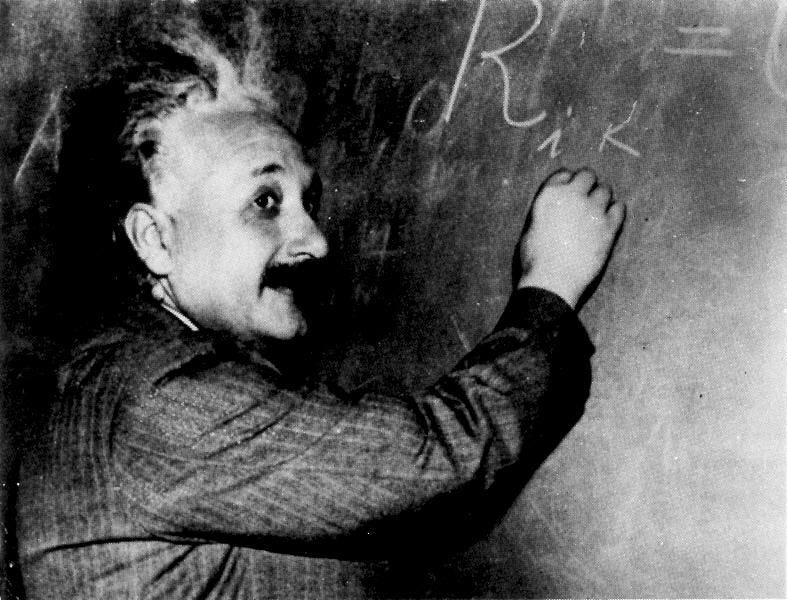

To clarify, one of Einstein's significant contributions in 1905 was his work on the photoelectric effect, which earned him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921—not for his theory of relativity. In this paper, he introduced the concept of light as discrete packets of energy, building on Planck's earlier ideas. This approach was quite revolutionary. Einstein's inclination leaned towards a deterministic understanding of the universe, embodying what is known as realism. This philosophical stance posits that objects and physical phenomena exist independently of observation. Essentially, even when not being observed, particles should still be regarded as existing, a notion that quantum mechanics also addresses.

As the field developed, a probabilistic interpretation emerged, particularly exemplified by the Copenhagen Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics. I have discussed this concept in previous articles, so I won’t delve into it too deeply here. In essence, this interpretation suggests that particles exist in various states until they are observed, with their behavior described by a wave function. The idea that a system can inhabit multiple quantum states simultaneously—collapsing into a definitive state only upon measurement—was something that puzzled Einstein greatly.

Chapter 2: The Challenge of Quantum Entanglement

Quantum phenomena such as entanglement, where two particles remain connected regardless of the distance separating them, further challenged Einstein's views. In this scenario, measuring one particle can instantly provide information about the state of the other, seemingly violating the established principles of relativity. This concept perplexed Einstein, who struggled to accept quantum mechanics as a definitive theory of reality, viewing it instead as an approximation that fell short of capturing nature's true essence.

In a letter to physicist Max Born in 1926, who was a proponent of the Copenhagen Interpretation, Einstein expressed his reservations:

“Quantum mechanics is certainly imposing. But an inner voice tells me that it is not yet the real thing. The theory says a lot, but does not really bring us any closer to the secret of the ‘old one.’ I, at any rate, am convinced that He does not throw dice.”

The original German phrase has been translated here, yet the core sentiment remains intact. The "God" Einstein references is not the traditional concept of an all-powerful deity, but rather the God of Spinoza—a philosophical perspective that emphasizes a rational universe governed by laws.

Thank you for taking the time to read this discussion. If you enjoyed it, please consider showing support by clicking the clap icon. For those interested in further supporting my work, consider becoming a Medium member through the provided link or buy me a coffee. Stay tuned for more insightful articles!