Can Science Answer Every Question? Exploring Limits of Knowledge

Written on

Chapter 1: The Role of Science in Knowledge Acquisition

Science has significantly altered our understanding of the world. Over the course of human history, especially in the last few centuries, we have witnessed profound transformations through scientific advancements. The scientific method has emerged as one of the most dependable means for acquiring knowledge and resolving factual disagreements (perhaps second only to mathematics).

Given its reliability, can we assert that every question is answerable through scientific inquiry, meaning via the scientific method applied to evidence? If this is the case, then we could claim to possess all knowledge available in a trustworthy manner. Conversely, if it is not, we must ask: can we comprehend anything that isn't accessible through scientific means?

Before delving into these inquiries, it's essential to clarify our terminology. Many people today seem to conflate knowledge with scientific discovery. However, that interpretation would render our discussion a tautology: to know equates to knowing through science. If that were the case, we might as well conclude our exploration here.

Epistemology, the branch of philosophy focused on the nature of knowledge, provides a framework for understanding what it means to know something. For the purpose of this discussion, I will define knowing as being reasonably justified in one’s beliefs.

The term "reasonably justified" here refers to justification based on logical reasoning, rather than emotions, intuitions, dreams, authority figures, or personal experiences. In the Socratic tradition, logic involves deriving conclusions from a set of reasonable premises. If your premises are valid, your terms are well-defined, and your reasoning is sound, you can justifiably arrive at your conclusion.

Where do these premises originate? They can stem from data, but not exclusively from scientific data. They can be drawn from any information we gather about our surroundings, encompassing mathematical truths, moral assertions (like "it is good to do good"), or causal inferences about the universe. These premises often have a commonality: they are generally accepted by rational individuals, as few would endorse their negation (although some do, constructing entire philosophies based on those premises). Making logical deductions based on universally rejected premises is counterproductive.

The inquiry isn't whether it's possible to know something without employing science. As I mentioned, knowing doesn't equate to scientific acquisition. Instead, the real question is whether all knowable truths can be derived through scientific methods, while acknowledging that such truths may also be obtained through less reliable means.

This question can be quickly addressed since the foundational assumption of science is that it operates within a consistent and repeatable framework governed by specific rules that validate experimental evidence. Absent this assumption, the scientific method would falter. We, as rational beings, accept the premise of science's existence, which we can classify as knowledge; yet it is not derived from scientific processes.

Another foundational principle is Ockham's razor, articulated by the 13th-century philosopher Willem of Ockham. He asserted that one should not multiply hypotheses unnecessarily, advocating for the simplest explanation that accounts for all evidence. Ockham's razor is axiomatic; no evidence directly supports it, yet it is self-evident, and rational people generally accept its validity. It plays a crucial role in the evolution of scientific thought.

Furthermore, the realm of mathematics represents a domain that can be regarded as more reliable than any conclusions drawn from the scientific method. We know that 2+2=4 with absolute certainty, a statement that cannot be claimed for any scientific theory.

Logic, the foundation of mathematics, is likewise presumed to be real. There is no definitive proof to establish the existence of rationality; it could simply be an evolutionary illusion crafted by our cognitive processes. Logic is inherently linked to some form of language—whether verbal, notational, or visual. Language distinguishes humans from inanimate entities. Could it be that logic and language are merely evolutionary adaptations?

However, how many rational individuals would accept this notion? Perhaps a few materialist philosophers might, but the average person, mathematicians, and scientists likely wouldn't.

Consider moral truths, such as the idea that it is good to act morally. While Nietzsche and a few others might dispute this, the majority of reasonable people would endorse it. Yet, can science definitively resolve that matter? Can you empirically disprove Nietzsche? The negative outcome of that axiom doesn't provide proof; it merely indicates that we accept the initial premise, labeling the results as "horrific," which implies they are negative.

Science lacks jurisdiction over abstract concepts, but what about notions related to the universe itself? Let's examine cause and effect. It has long been accepted that causes precede effects. This assumption underlies the classic Prime Mover argument for the existence of God. However, quantum mechanics experiments suggest that causation can be reversed. Does this signify that science has disproven a philosophical axiom that is supposed to be immune to scientific scrutiny, or is it merely a matter of vague definitions?

In these quantum experiments, it may be unclear whether the effect follows the cause or vice versa. Nonetheless, it remains impossible to create a paradox, such as a time travel scenario that would genuinely violate causality. In terms of measurable cause-effect relationships, causality is preserved, even in these experiments. Thus far, we haven't demonstrated a true violation of causality, and our understanding of cause and effect in the context of quantum mechanics versus classical interpretations may need refinement.

While the scientific method presupposes causality (which is itself a testable scientific hypothesis, albeit one unlikely to be false), it can never prove it to be true. In fact, science cannot establish absolute truths in the same manner that mathematics can. Scientific theories are not strictly true or false; they are better or worse representations of reality.

Philosopher Karl Popper articulated this in his theory of falsifiability. Science operates by observing unexplained phenomena, proposing plausible hypotheses, and testing each until only one remains. That hypothesis is then considered factual. However, new hypotheses can be formulated that explain more and potentially invalidate previous ones. This occurred in 1919 when Einstein's general relativity was confirmed to accurately predict light bending around the Sun, thereby disproving Newton's gravity theory, which could not account for this phenomenon.

Popper's insights suggest that science does not affirm truths but rather distinguishes superior theories from inferior ones, akin to how Ockham's razor evaluates hypotheses. Consequently, relativity represents not an absolute truth but our most reliable theory, which we continually strive to challenge to foster the development of more accurate explanations.

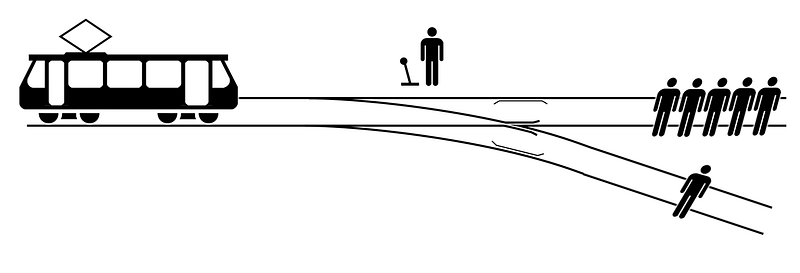

Popper's framework can also be applied to non-scientific domains, like moral philosophy, where the standard for evidence is not experimental but rooted in people's inherent moral beliefs. Analyzing what reasonable individuals consider right and wrong aids in "falsifying" our moral premises. Moral philosophers often conduct studies presenting participants with ethical dilemmas, such as the "trolley problem": if a runaway trolley is headed towards five people, would you pull a lever to divert it to a single individual?

Most individuals would opt to pull the lever, yet altering the scenario in various ways adds complexity. For instance, if it required physically pushing someone in front of the trolley to save five, many would refrain. If the one person were a loved one, again, most would struggle to adopt a utilitarian perspective.

Consider the moral dilemma surrounding organ donation: is it ethical to kill one person, harvest their organs, and save five others? The majority would likely say no. If that individual had died without consenting to organ donation, would that change opinions? Moral questions are nuanced, and to be coherent, premises must be explicitly defined in terms of the specifics involved. Philosophies like strict utilitarianism, which posit maximizing overall happiness, often falter under scrutiny from reasonable premises.

This demonstrates that while the scientific method may enhance our conclusions about seemingly unscientific matters, such as morality, it cannot provide the same level of reliability as studies in physics or chemistry. Its role is to accumulate data to better understand public beliefs but cannot render those beliefs inherently scientific.

When addressing existential questions like the existence of God, reasoned premises and logical deductions allow us to draw significant conclusions. Many arguments against God's existence were formulated by Christian thinkers like St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas, who sought to test the robustness of their beliefs logically. A classic philosophical conundrum presents four statements about God: God exists; God is all good; God is all powerful; and evil exists.

This presents a paradox, as not all these statements can coexist; at least one must be false. The reasoning posits that an all-good and all-powerful God would not permit evil.

Atheists typically dispute the first assertion: God exists. Few would deny the existence of evil. Can science provide evidence of evil? No, as evil pertains to human actions, and science refrains from making moral judgments about these actions. This inquiry requires human perspectives.

Buddhists might contend that the first statement lacks a definitive answer, while Hindus may question the second. Other polytheists might refute both the second and third statements. Adherents of Abrahamic faiths—Christianity, Judaism, and Islam—are less likely to outright reject any of these claims. Instead, they may argue that the terms are poorly defined or that the conclusion asserting an all-good, all-powerful God would prevent evil is flawed. The Book of Job illustrates this argument, where God tells Job, "Do not question me; I have my reasons." Some posit that the evils present in the world serve a greater purpose, acting as necessary trials leading to salvation and eternal bliss.

Further, some contend that evil is a human construct rather than a divine one. God created humanity with the gift of free will, allowing individuals to choose between good and evil. This argument, found in the Book of Genesis, does not adequately address why bad things happen to good people.

Some Christians argue that through Christ, God is ultimately subduing evil, suggesting that overcoming evil is a more profound act than simply preventing its existence. Thus, allowing evil could be seen as a means for God and humanity to achieve greater good.

Numerous additional arguments could be explored, but science has limited contributions to this discourse. It cannot disprove God's existence unless one links belief in God to a specific scientific theory, an unreasonable position. Similarly, the basis for science’s existence cannot be validated through scientific means, just as the existence of God cannot be confirmed or denied through scientific inquiry. Science can illustrate the diverse moral standards across human societies, revealing instances where every one of the Ten Commandments is routinely violated. However, it remains challenging to argue against the presence of moral standards altogether. Most rational individuals would be reluctant to embrace the implications of such a belief, as it might justify heinous actions. Once one accepts that no moral standard exists, the only restraint left is the extent to which society is willing to counteract those actions. In such a scenario, power dictates morality.

In conclusion, while science may not provide all-encompassing knowledge, it can inform answers to vital questions, such as: What constitutes right and wrong? How do we acquire knowledge? Is there a God? These inquiries can be approached through logic and critical questioning based on sound premises. Although some might contend that we are merely engaging with subjective beliefs, few would maintain that all human knowledge is purely subjective. Some may argue that the notion of objective knowledge is a convenient fiction, upheld because the consequences of rejecting it are too dreadful to fathom. This thought is indeed worth contemplating; however, it suggests that the assertion of subjective knowledge is itself a subjective claim, rendering it amusingly paradoxical and difficult to justify.

In this exploration, I aimed not to provide a formal analysis but rather to navigate the complexities of the topic, allowing for flexibility in terms and arguments. A multitude of alternative philosophies and counterarguments can be applied to any of these points. Such diversity is beneficial; having more objections and arguments enriches our understanding, akin to science's pursuit of knowledge through varied data collection, even if the realms of philosophy and science differ in reliability.