Understanding Compactification: A Deep Dive into Spacetime

Written on

Chapter 1: Introduction to Compactification

Infinite spaces can be perplexing, making it challenging to apply rigorous mathematical or physical principles. In the realm of physics, the strategy often involves compressing these extensive, infinite structures into more manageable finite forms. For instance, one might attempt to condense an infinite two-dimensional expanse into a bounded area.

In the context of general relativity, this approach is frequently employed to clarify the causal relationships within a given spacetime. The term "causal structure" refers to understanding how various events can influence one another physically. This article will outline how physicists effectively reduce larger spaces into smaller ones through a method known as compactification. Additionally, I will explain how these compactified regions are represented using a visual tool called Penrose diagrams.

This discussion will delve into technicalities, but I will aim to clarify the mathematical elements as thoroughly as possible.

Conformal Transformations

In general relativity, the backdrop for events is termed spacetime. This spacetime is typically defined by a metric that quantifies the length of vectors within it. As noted earlier, physicists often encounter a spacetime M characterized by a metric g. We can alter this metric by scaling it with a positive number to facilitate calculations. This process is known as a conformal transformation.

The equation below illustrates a conformal transformation. On the left side, we depict the 'transformed' metric, represented with a curly line above. The scaling transformation is indicated by the Greek letter ?(x) on the right side. For a transformation to qualify as conformal, the function ?(x) must be smooth and non-zero across its domain. The rationale behind this requirement will be explained in the subsequent section.

Thus, we take a metric and adjust it using a function ?(x) that adheres to a loose set of criteria. Generally, we anticipate that the new metric will appear significantly different. These metrics may not share the same symmetries; they typically describe distinct spacetimes.

However, they do share a crucial commonality: in both general and special relativity, null vectors, which possess zero length, describe entities moving at light speed, like photons. A vector deemed null in the spacetime with metric g remains null in the g˜ spacetime, indicating that their causal structures are equivalent.

In the equation to the left, we measure the length of vector X in the first spacetime. If the size of X is zero, given that the scaling factor ?(x) is positive and non-zero, it implies that in the new metric, a vector that initially had zero length maintains that property.

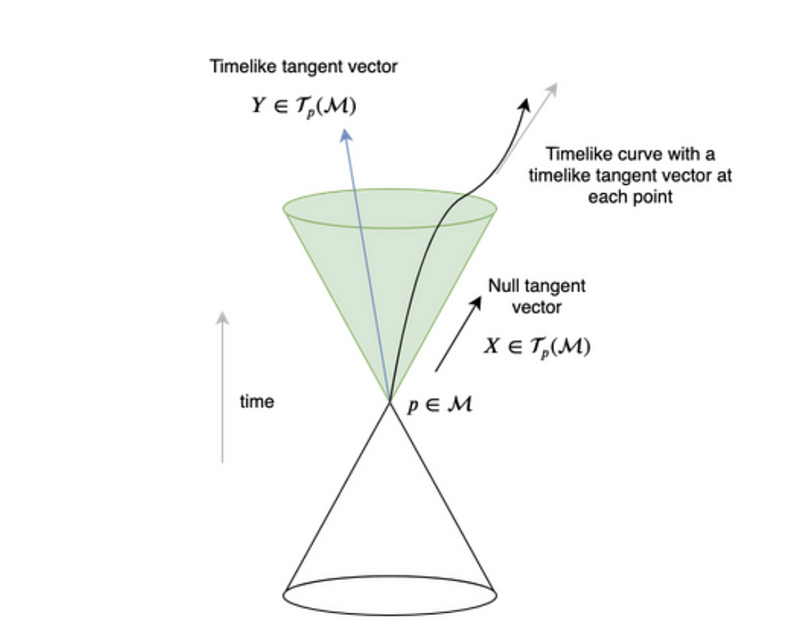

In the realm of spacetime, null vectors differentiate regions that are time-like or space-like relative to our 'origin point.' Time-like vectors yield negative lengths, while space-like vectors result in positive lengths. An observer at the origin can influence events along time-like vectors but cannot affect those along space-like vectors.

Since null vectors serve as the dividing line between positive and negative lengths, we find that null/space-like/time-like vectors in g correspond to null/space-like/time-like vectors in x˜. This leads us to a remarkable conclusion: despite the apparent differences in metrics, the causal structure of spacetime remains unchanged under conformal transformations. Such transformations are prevalent throughout physics.

Changing Our Perspective

The objective is to utilize conformal transformations to bring the concept of infinity in spacetime 'closer,' enabling a clearer visualization of its nature. While there are sophisticated methods for creating these diagrams, we will explore examples to grasp the concept. To start, we will tidy up our approach with some coordinate transformations.

In Minkowski space with one time and one space dimension, the metric defining the distance between two nearby points is expressed as ds²= ?dt² +dx² (the standard metric). To make this more manageable, we will reframe this metric using an alternative set of coordinates. At this juncture, we are not yet discussing conformal transformations, which are actual physical modifications to our metric. We are merely shifting our perspective.

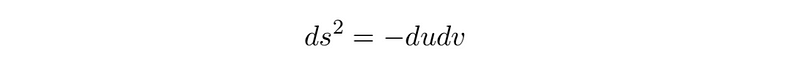

We will implement two consecutive coordinate transformations to simplify the metric. We introduce light-cone coordinates u = t - x and v = t + x. With basic calculations, our original Minkowski metric is reformulated. It is evident that in these coordinates,

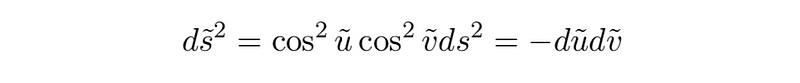

We must pay careful attention to the ranges of the coordinates. Specifically, we have u, v ∈ (−∞, ∞), as t and x share the same range. The goal is to develop a second coordinate transformation that maps the infinite ranges of u and v to finite intervals. We can select any function possessing an infinite range but a finite domain. A straightforward choice is the tangent function.

As a result, the ranges of our variables u and v become finite, confined to the interval (−π/2, π/2). By differentiating one forms, physicists can now express the new metric as follows:

This configuration is promising because it resembles a conformally equivalent form of our light-cone coordinates, while also ensuring that u and v are both within a finite range. Next, we will apply a conformal mapping to eliminate the scaling factor by multiplying it with its reciprocal. This yields a new conformally transformed metric.

Consequently, we obtain a structure akin to the Minkowski metric, albeit with a limited range. We express this range to include the closure of the set (which acts as infinity), ensuring that u and v ∈ [−π/2, + π/2]. Incorporating the points ±∞ that were previously ±∞ is termed conformal compactification.

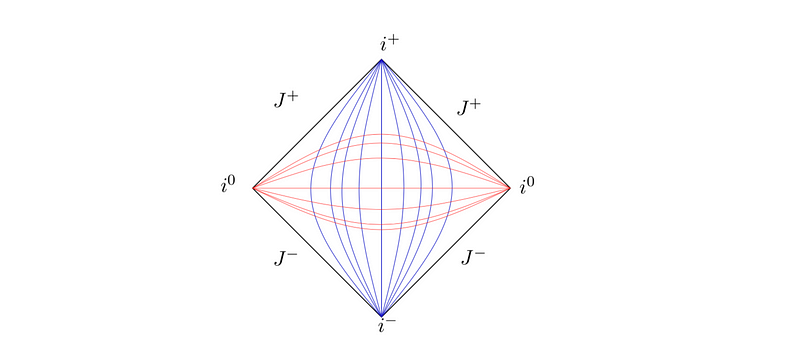

Next, we will endeavor to create a visual representation of this spacetime. A common guideline in general relativity is to depict light-cone coordinates at 45 degrees. This principle applies to Penrose diagrams, so we will illustrate the coordinates in a diamond shape within the range (−∞, ∞). In this coordinate system, time is oriented vertically.

Exploring Penrose Diagrams

The diagram presented above is a Penrose diagram. While distances on these diagrams should not be trusted, the causal structure can be relied upon. Geodesics represent the trajectories of particles in spacetime. What does a general geodesic look like in this context? We derive the geodesic using the Lagrangian shown below.

Substituting this into our new light-cone coordinates reveals that all geodesics, when expressed in terms of the coordinates (u, v), approach (−π/2, π/2) as we look further into the future. Similarly, they converge to (−∞/2, ∞/2) as we look sufficiently far into the past.

We can illustrate various geodesics on this diagram, particularly time-like geodesics with constant x and space-like geodesics with constant t (other geodesics exist, but these will be the focus in the following figure). These geodesics correspond to our original metric choice.

All time-like geodesics, indicated by blue lines in the diagram above, originate at the point i− and conclude at i+. These are referred to as past and future time-like infinity. Conversely, space-like geodesics begin and end at two points i−, which are located at [−∞/2,+∞/2] or [+∞/2, −∞/2]. These points are termed space-like infinity. Lastly, all null curves initiate at J−, labeled “scri-minus,” and terminate at J+, labeled “scri-plus.” Diagonal lines on the Penrose diagram represent these null curves, known as past and future null infinity.

The aforementioned aspects are easily discernible from a Penrose diagram, underscoring their utility as a powerful tool for physicists to interpret the causal structure of spacetime. They convey fundamental insights about spacetime, such as the exciting yet non-obvious fact that every two points in spacetime share a common future and past.

This brief overview scratches the surface of this fascinating topic, so stay tuned for more discussions to come!

Chapter 2: Video Insights on Compactification

The first video explores the concept of compactification in higher-dimensional physics, providing insights into how physicists manage infinite spaces.

The second video delves into the process of compactifying extra dimensions, further elucidating the principles discussed in this article.

References

[1] The Large Scale Structure of Space–Time, S. W. Hawking, G. F. R. Ellis. Publisher: Cambridge University Press