Why Some Individuals Struggle to Wink: An Intriguing Look

Written on

Understanding the Mechanics of Winking

Imagine you're at a bar, and someone captures your attention. You glance their way, and suddenly, they lock eyes with you. Your cheeks flush, and just as you think about how to respond, they give you a playful wink. This scenario took a twist for me when I realized my future wife couldn't wink at all. Instead of a wink, I saw her emphatically blinking. It was this moment that sparked my curiosity about the underlying mechanisms that differentiate a wink from a blink.

Research indicates that while most individuals can wink with either eye, some struggle to do so. Traditionally, it was thought that the ability to wink was hereditary. However, a 2019 study published in the journal Brain and Behavior examined individuals who could wink but demonstrated varying levels of proficiency. Interestingly, half of those who could initially wink with just one eye learned to wink with both eyes within a month, suggesting that winking is a skill that can be developed.

Blinks vs. Winks: What’s the Difference?

Blinks are rapid closures of the eyelid, occurring unconsciously around 15 times a minute. They serve to protect and lubricate the eyes, preventing dryness. There are three primary types of blinks:

- Reflexive Blinks: These occur automatically in response to external stimuli.

- Voluntary Blinks: These are consciously controlled.

- Spontaneous Blinks: The most common type, these happen without any specific trigger.

The speed of eyelid closure varies with the type of blink, with reflexive blinks being the quickest and spontaneous ones the slowest. Spontaneous blinking is primarily regulated by the frontal lobe, while voluntary blinking involves different pathways in the brain.

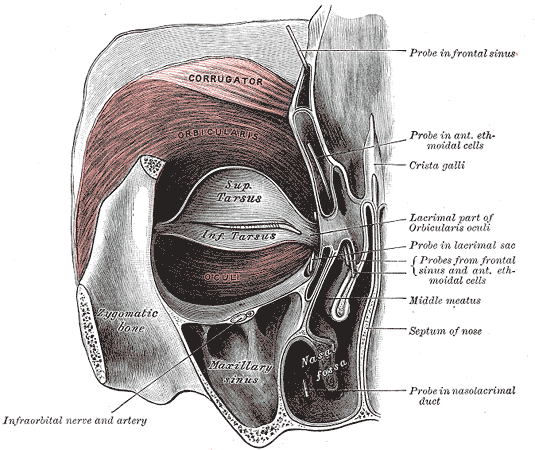

The Anatomy of Winking

A wink involves the contraction of the orbicularis oculi muscle that encircles the eye, controlled by the buccal branch of the facial nerve. Additionally, the levator palpebrae superioris elevates the eyelid during contraction, under the control of the oculomotor nerve.

When there’s damage to these nerves, such as in Bell’s Palsy, it can hinder the ability to close one eye because the affected side's muscles can’t contract properly. This illustrates the localized control of eyelid movement, as well as the broader brain regions involved in these actions.

Winking: A Complex Brain Process

Interestingly, controlling a blink is more challenging for the brain than simply allowing it to happen. While spontaneous blinking activates the frontal lobes, consciously suppressing a blink engages multiple brain areas, including the parietal, occipital, and temporal lobes.

Moreover, the brain regions involved in winking vary depending on which eye is used. For individuals unable to wink with their left eye, attempting to do so activates both frontal lobes, but the left side plays a more significant role. Conversely, those who can't wink with their right eye see activation solely in the right frontal lobe.

In stroke patients who lose the ability to open their eyelids, studies indicate that only the right hemisphere of the brain is typically affected. This suggests a strong influence of the right cerebral hemisphere in eyelid control. A study involving 27 stroke patients found that 70% had lesions in the right insular cortex, a region associated with various functions, including sensory processing and emotional representation.

The intricate control of eyelid movement by such a complex brain region may explain why winks are interpreted as emotional signals.

So, when my wife blinked at me, I understood it as a gesture of love—double the affection, perhaps.

The video titled "I Can't Wink??? Learning How to Wink" explores the mechanics of winking and features various attempts at mastering this skill, reinforcing the idea that winking can indeed be learned.